jeudi, 10 janvier 2013

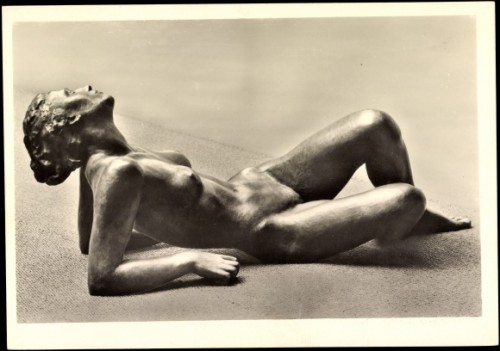

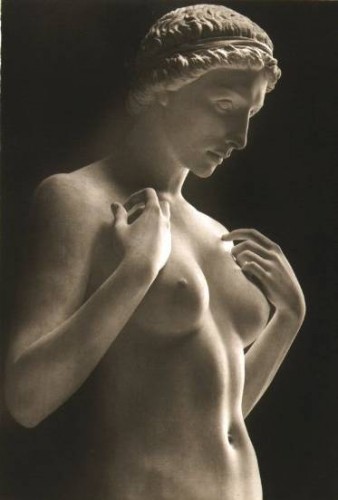

Fritz Klimsch: Sonnenbad/Bain de soleil

Fritz Klimsch

Sonnenbad/Bain de soleil

00:05 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | Tags : art, allemagne, sculpture, arts plastiques, art néo-classique, néo-classicisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 25 novembre 2012

Parc Vigeland, Oslo

Parc Vigeland, Oslo, 6 & 7 août 2011

Photos de Robert Steuckers

6 août, journée ensoleillée et torride, excellente lumière

00:06 Publié dans art, Photographies, Photos | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : photographies, photos, vigeland, oslo, norvège, robert steuckers, art, sculpture, arts plastiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 23 janvier 2012

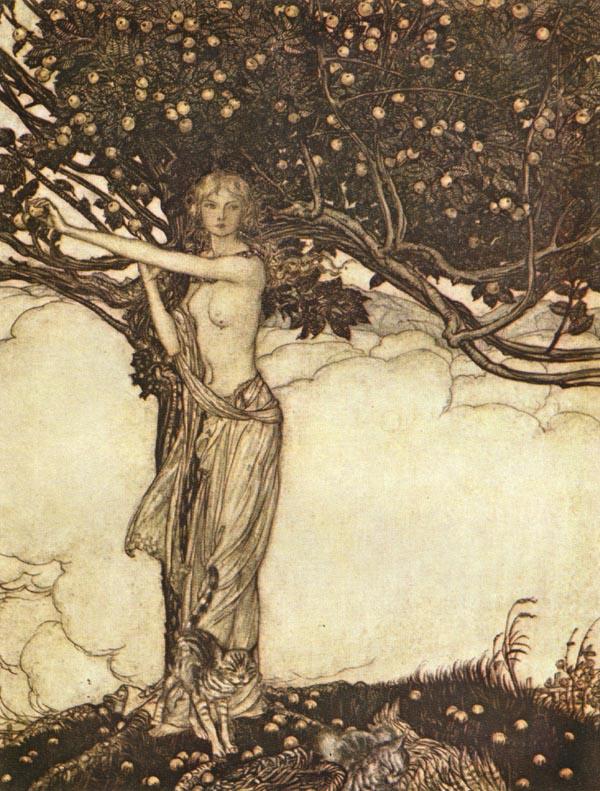

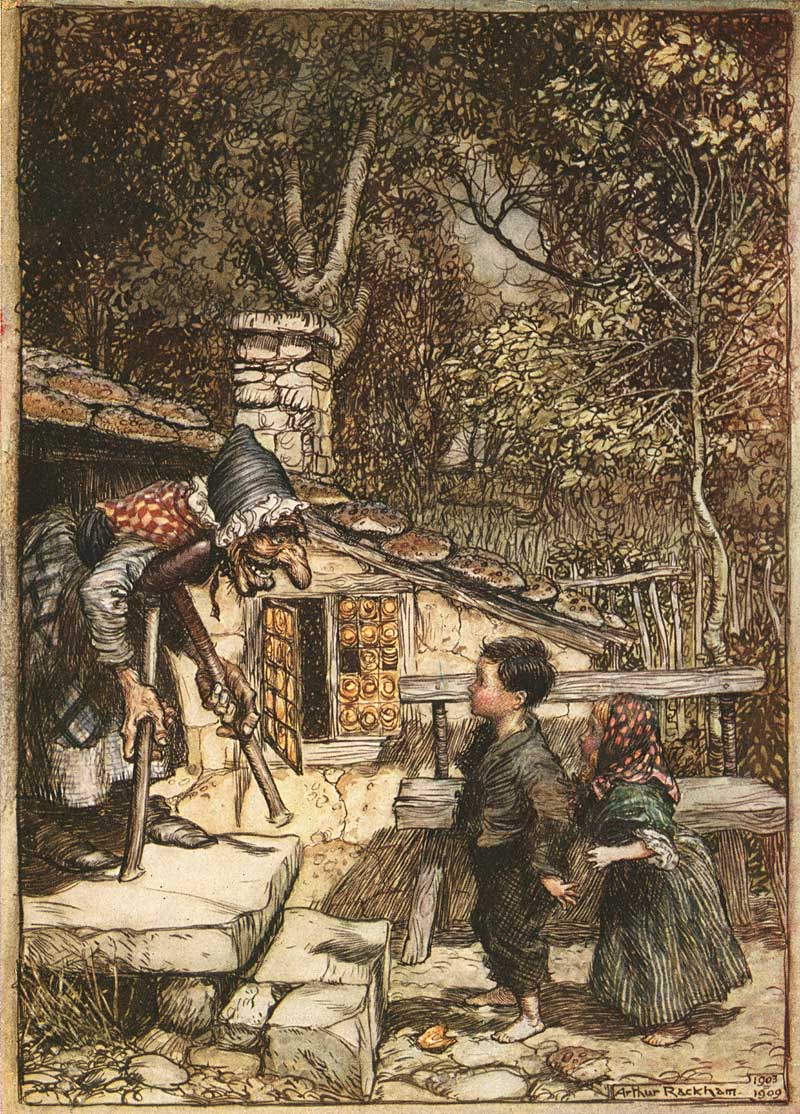

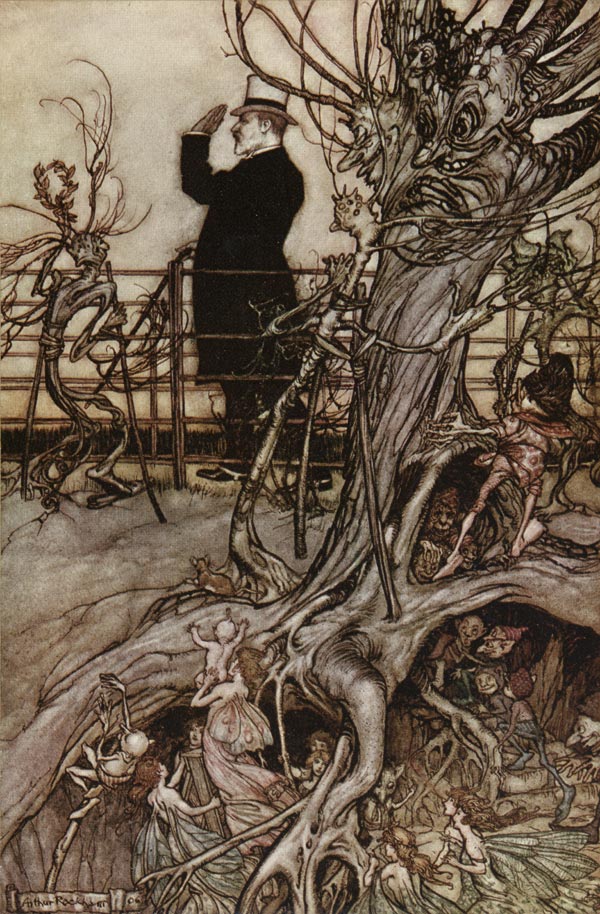

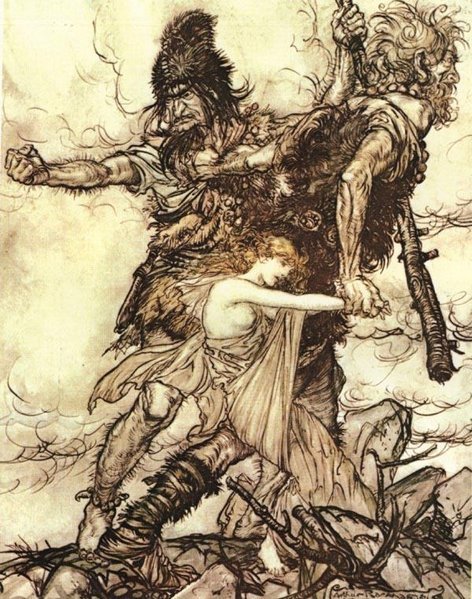

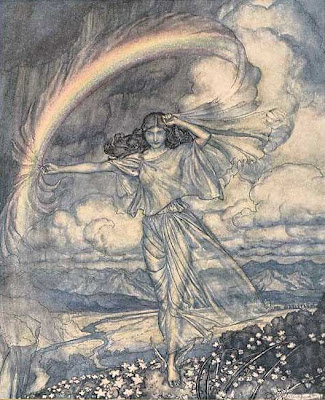

A Arte de Arthur Rackham

A Arte de Arthur Rackham

Ex: http://legio-victrix.blogspot.com/

00:05 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : art, arts plastiques, peinture, dessin |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 08 janvier 2012

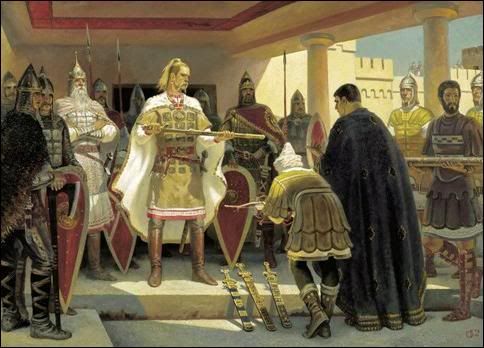

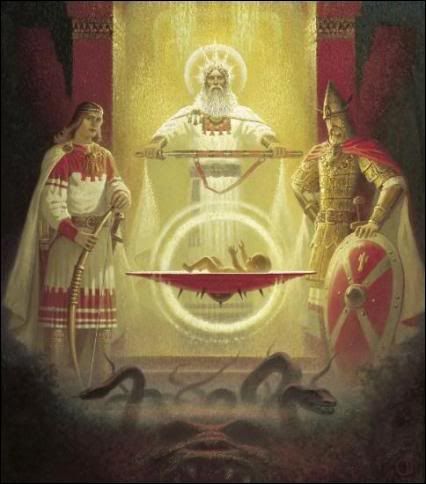

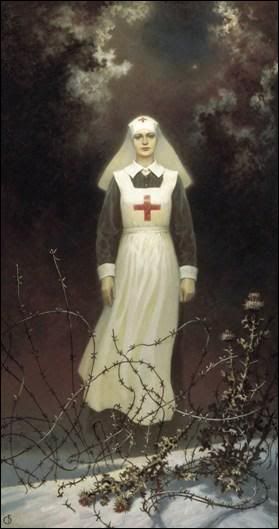

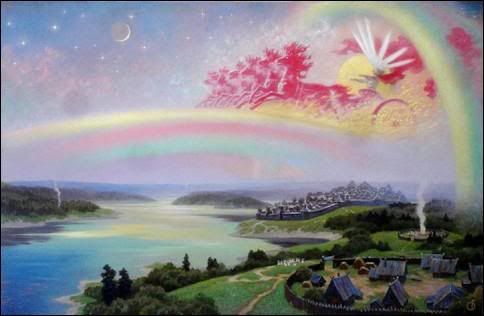

El arte de Boris Olshansky

El arte de Boris Olshansky

Ex: http://europa-soberana.blogia.com/

El disfrute de la belleza y del orden, por el mero placer de la contemplación, sin ningún sentido práctico, es quizás uno de los argumentos más elocuentes a favor de la existencia del espíritu. El arte bien entendido viene a ser una fuente de nostalgia, anhelo, inspiración, idealismo y esperanza, la lucha del espíritu por evadirse del orden material y volver a elevarse a lo alto por unos instantes.

El artista que nos ocupa en esta ocasión viene a ser otro pintor ruso, Boris Mijailovich Olshansky, nacido el 25 de Febrero (Piscis) de 1956 en Tambov, una ciudad mediana del oeste de Rusia. Su madre, campesina, sumamente tradicional y devota, tuvo cinco hijos además de él. Su padre era un veterano de guerra herido en combate (la bala de un francotirador alemán le entró por una mejilla y le salió por un ojo) y que disfrutaba del apoyo estatal para gente de su condición.

Aunque se crió durante la época soviética, en la que poco menos que parecía que la historia de Rusia comenzaba en 1917 con la revolución bolchevique, Olshansky escribe que "la misma vida, nuestra mente y nuestra memoria genética, buscan intensamente las fuentes de la cultura y la historia".

Boris M. Olshansky.

Enseguida apreciaremos los rasgos básicos del arte de Olshansky: nacionalismo ruso, paneslavismo, idealización del pasado proto-eslavo y de los rasgos nórdicos, menciones a los antiguos griegos, vikingos, bizantinos y otomanos, fuerte carga paganizante pero sin renunciar a la fe ortodoxa, concepción de Rusia como un muro de contención ante las hordas asiáticas, importancia de la Naturaleza, ausencia total de "ideales modernos", etc. A diferencia del ya visto Konstantin Vasiliev ―que hizo algunos guiños al "comunismo patriótico"―, la obra de Olshansky carece totalmente de simbología soviética.

Este arte no parece gran cosa si lo comparamos con el Renacimiento, con el Siglo de Oro español o con la época victoriana, pero hay que recordar que estamos en el Siglo XXI, el siglo de la globalización capitalista neoliberal, de la humanidad-masa, de la vulgarización, del gran asalto de la materia inerte (sin espíritu) sobre la materia viva (con espíritu) y en la disolución de toda forma de tradición.

Por tanto, es notable que aun existan personas volcadas en producir arte de verdad y no basura abstracta que sólo sirve para establecer "fundaciones" privadas, exposiciones y museos de "arte moderno", donde un público descerebrado y esnob se dedica a contemplar con devoción excrementos enlatados, escombros fundidos, vacas mutiladas o salpicaduras de pintura hechas por algún cocainómano. Además, en torno a estas instituciones de "arte moderno" han florecido importantes negocios de lavado de enormes cantidades de dinero negro ―procedente del narcotráfico, la trata de blancas, el tráfico de armas y de órganos, la especulación, etc.

Sin más, veamos algunas de las obras de este pintor. En todas las imágenes, click para agrandar.

"Paisaje" (años 80).

"El campo de Kulikovo" (1994). Rusia también tuvo monjes-soldados comparables a los caballeros de las órdenes religioso-militares de Europa Occidental. El personaje representado es Peresvet, un monje que se batió en duelo contra un jinete mongol antes de la batalla de Kulikovo. Ambos morirían en el choque, pero el mongol cayó de su caballo, el ruso no.

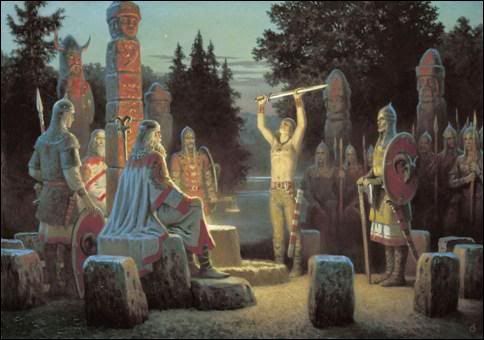

"La leyenda de Sviatoslav" (1996). Sviatoslav I de Kiev fue un konung (príncipe) pagano del Estado de Rus de Kiev, que vivió en el Siglo X y que derrotó a los jázaros y los búlgaros. De origen varego (vikingo sueco), llegó al Caspio y a las puertas del Imperio Bizantino.

"La batalla del Dnieper" (1996). Sviatoslav se enfrenta a los jázaros. El emperador bizantino Constantino VII consideraba que quien controlara las cataratas del Dniéper podría destruir los barcos rusos.

"Una verdadera historia eslava" (1997).

"Nacimiento de un héroe" (1997).

"Iván el hijo de la viuda" (1999).

"La noche del héroe" (1999).

"Bereginya" (1999).

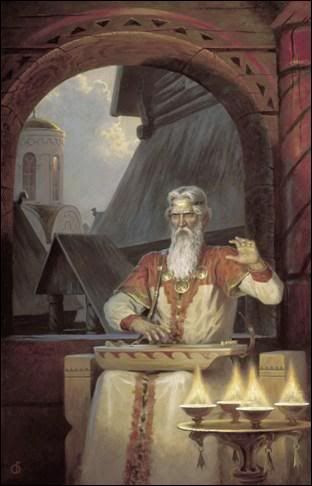

"Svarog" (fecha desconocida). Svarog era un dios uránico (celeste) eslavo.

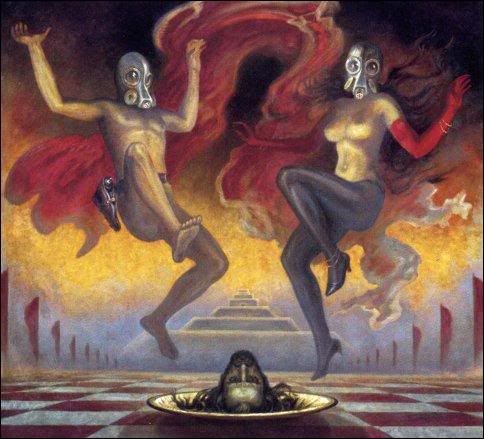

"El sueño de la razón produce monstruos" (fecha desconocida). No confundir con el grabado homónimo del pintor español Goya.

"Marchando sobre Tsargrad el verano de 908" (fecha desconocida). "Tsargrad" (es decir, "Cesargrado", la ciudad de los Césares), era la forma que tenían los antiguos eslavos de referirse a Constantinopla, la capital del Imperio Bizantino, actualmente capital de Turquía y llamada Estambul. Por aquel entonces, Constantinopla tenía unos 750.000 habitantes, era la ciudad más importante del Mediterráneo y a menudo tenía que enfrentarse a las incursiones de los varegos (vikingos suecos asentados en lo que hoy son Rusia y Ucrania). Uno de ellos, el konung Oleg de Novgorod, lideró un ataque ruso contra Constantinopla.

"Escudos en la puerta de Tsargarad, la gloria de Rus" (fecha desconocida). La princesa bizantina le suplicó a Oleg que no entrase como enemigo y que se apiadase de la ciudad. El príncipe acepto y, al llegar a la ciudad, las puertas le fueron abiertas de par en par. Oleg obtuvo un importante tratado comercial, ordenó que su escudo fuese colgado sobre la puerta del palacio imperial bizantino y navegó de vuelta a Kiev con las riquezas obtenidas. La presencia vikinga en el Imperio Bizantino acabaría dando lugar a la Guardia Varega.

"Réquiem ruso" (fecha desconocida).

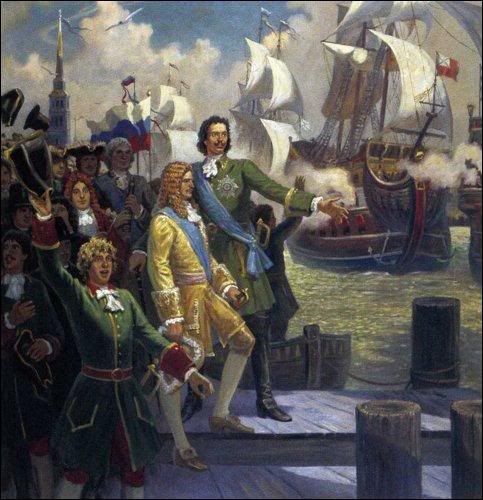

"El nacimiento de la flota rusa" (fecha desconocida). El zar Pedro el Grande estaba muy interesado en romper la continentalidad de Rusia dándole una salida al mar. Lo consiguió conquistando territorio sueco en el Báltico y turco en el Mar Negro. San Petersburgo fue fundada en 1703.

"Patio de una embajada, Siglo XVII" (fecha desconocida).

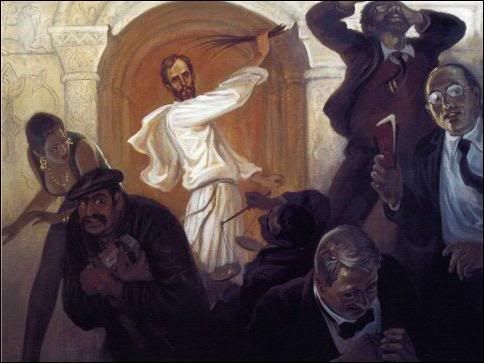

"El triunfo de los herodianos" (fecha desconocida). Los enemigos de Cristo celebran la muerte de San Juan Bautista. Junto con "El sueño de la razón produce monstruos", esta pieza, en palabras del artista, representa "la pobreza espiritual del mundo moderno".

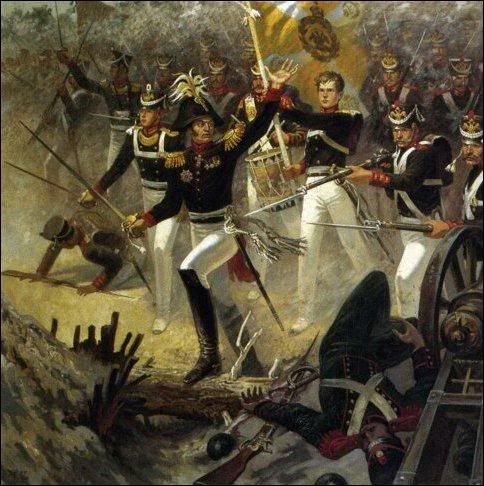

"La gesta de Raevsky" (fecha desconocida). El general Nikolai Raevsky fue un héroe ruso que se distinguió especialmente durante la invasión napoleónica.

"Sombras de antepasados olvidados" (2002).

"Noche de Kupala" (1995-2003).

"Juramento de Svarog" (2003).

"Desde las oscuras profundidades de los siglos" (2003).

"Gran Rus" (2005).

"Jesús y los cambiadores de dinero" (2006).

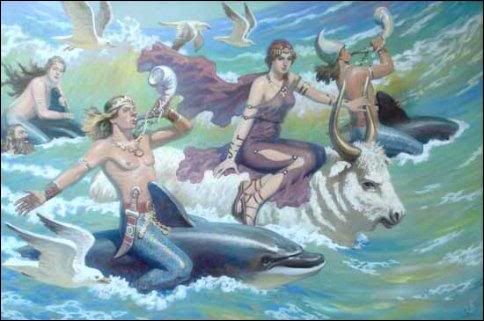

"El rapto de Europa" (2007).

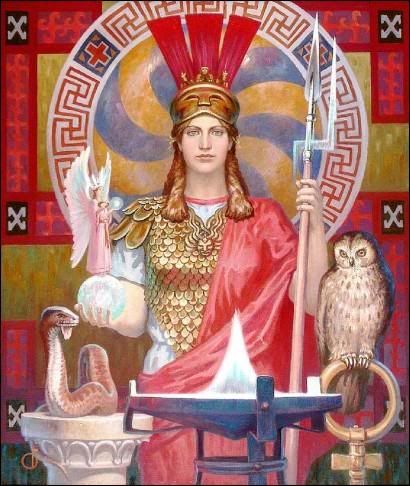

Estudio para "Diosa blanca de la sabiduría" (2009). Obviamente, se trata de la Atenea helénica.

"Diosa blanca de la sabiduría" (2009).

Título y fecha desconocidos.

Ídem. La deidad que cabalga por el cielo es Dazhbog, un dios solar eslavo.

Pueden verse más obras del artista en los siguientes enlaces:

http://01varvara.wordpress.com/category/fine-art/page/42/

http://galleries.tvalx.com/Russia/BorisOlshansky1/russian_artist_boris_olshansky.htm

http://ateney.ru/art/art006.htm?PHPSESSID=e4ab8614f4c6cbaa15bd65da349f7872

http://www.artcyclopedia.ru/olshanskij_boris_mihajlovich....

00:05 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : russie, art, arts plastiques, peinture |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 27 août 2011

Sculpture de Hugo Elmqvist

00:05 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : art, arts plastiques, sculpture |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 26 août 2011

Sculpture de Nils Hjalmar Mollerberg

00:05 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : art, arts plastiques, sculpture |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 25 août 2011

Tableau de Félix De Boeck

00:05 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : félix de boeck, art, arts plastiques, peinture |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 23 mai 2011

Nicholas Roerich

Nicholas Roerich

Nicholas Roerich and Alexander Borodin

00:05 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : art, russie, asie centrale, asie, eurasisme, eurasie, nicholas roerich, peinture, arts plastiques, himalaya |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 19 mai 2011

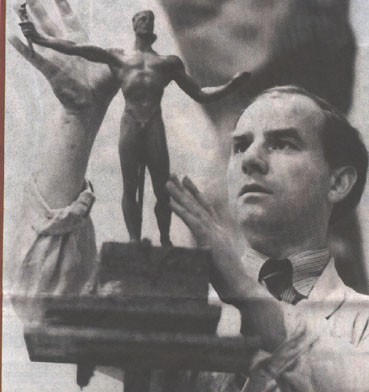

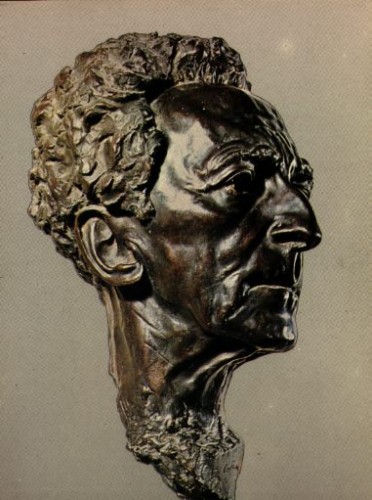

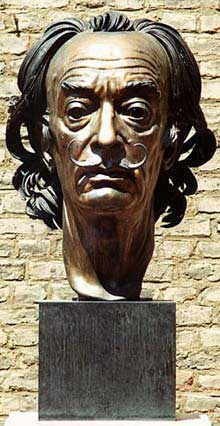

De Michelangelo van de 20ste eeuw

De Michelangelo van de 20ste eeuw

Ex: http://www.kasper-gent.org/

“Gott ist die Schönheit und Arno Breker sein Prophet.” (Salvador Dali)

Inleiding

Geen kunstenaar zo omstreden als Arno Breker. De Duitse beeldhouwer greep in de 20ste eeuw, op een moment dat Europa in de ban was van het modernisme, terug naar de renaissance en leverde uitzonderlijk werk af, zoals Bereitschaft en Berufung. Maar: Breker was een van Hitlers gefavoriseerde beeldhouwers – samen met onder andere Josef Thorak en Gerard Hauptmann – wat hem gedurende de naziperiode weliswaar faam opleverde (die verdiende hij trouwens); toch zou deze professionele band met Hitler voor hem na de val van nazi-Duitsland vooral het einde van zijn artistieke carrière betekenen. Breker bleef weliswaar beeldhouwen, maar vanwege zijn zwart verleden werd hij, zeker in Duitsland, doodgezwegen. Zo stelde de overheid pas in 2006 voor de eerste maal het gehele oeuvre van Breker tentoon en ook toen nog zorgde deze tentoonstelling voor heel wat opschudding in de Duitse media.

Geen kunstenaar zo omstreden als Arno Breker. De Duitse beeldhouwer greep in de 20ste eeuw, op een moment dat Europa in de ban was van het modernisme, terug naar de renaissance en leverde uitzonderlijk werk af, zoals Bereitschaft en Berufung. Maar: Breker was een van Hitlers gefavoriseerde beeldhouwers – samen met onder andere Josef Thorak en Gerard Hauptmann – wat hem gedurende de naziperiode weliswaar faam opleverde (die verdiende hij trouwens); toch zou deze professionele band met Hitler voor hem na de val van nazi-Duitsland vooral het einde van zijn artistieke carrière betekenen. Breker bleef weliswaar beeldhouwen, maar vanwege zijn zwart verleden werd hij, zeker in Duitsland, doodgezwegen. Zo stelde de overheid pas in 2006 voor de eerste maal het gehele oeuvre van Breker tentoon en ook toen nog zorgde deze tentoonstelling voor heel wat opschudding in de Duitse media.

Het begin van een artistieke carrière

In 1927 – hij was toen 27 jaar – trok Breker naar Parijs waar hij contacten legde met verschillende Franse en internationale kunstenaars, zoals Charles Despiau, Aristide Maillol en Ernest Hemmingway, die hem inspireerden en stimuleerden. Breker had het geluk de kunsthandelaar Alfred Flechtheim te hebben leren kennen. Door zijn contacten met Flechtheim ontving Breker al snel vele opdrachten uit binnen- en buitenland en bouwde zo op zeer korte tijd een stevige reputatie uit. In 1932 werd aan Breker de Rom-Preis des preußischen Kultusministeriums uitgereikt wat het voor hem mogelijk maakte zelf naar Rome te trekken. Daar raakte hij enorm onder de indruk van Michelangelo en de stedenbouw, elementen die later in zijn neoclassicistische ontwerpen voor het Derde Rijk zouden terugkomen.

Op dat moment toekomstig Minister van Propaganda Joseph Goebbels, die Breker in Rome had leren kennen, drong er bij hem op aan om terug te keren naar Duitsland, omdat “er hem een grote toekomst te wachten stond”. De jonge en ambitieuze Breker aarzelde niet, zeker niet toen schilder en goede vriend Max Lieberman hem daar ook nog eens toe aanzette. In 1934 keerde Breker terug naar zijn vaderland, waar hij alle voordelen genoot van een protegé van het regime.

Op dat moment toekomstig Minister van Propaganda Joseph Goebbels, die Breker in Rome had leren kennen, drong er bij hem op aan om terug te keren naar Duitsland, omdat “er hem een grote toekomst te wachten stond”. De jonge en ambitieuze Breker aarzelde niet, zeker niet toen schilder en goede vriend Max Lieberman hem daar ook nog eens toe aanzette. In 1934 keerde Breker terug naar zijn vaderland, waar hij alle voordelen genoot van een protegé van het regime.

De Olympische Spelen van 1936

Met de Olympische Spelen van 1936 in Berlijn draaide de Duitse propagandamachine op volle toeren. Hoewel het Olympisch handvest door de nazi’s nageleefd werd, zag men de Spelen toch als een uitgelezen kans om de nationaal-socialistische ideologie uit te dragen. Voor Arno Breker betekenden de Spelen een nieuw hoogtepunt in zijn carrière. Zijn beelden Zehnkämpfer en Die Siegerin, beide beelden meer dan drie meter hoog, behaalden een zilveren medaille. De jury had hem de gouden medaille willen geven, maar Adolf Hitler wilde vanwege politiek-strategische redenen per se dat een Italiaan die gouden medaille zou krijgen. Toch stak Hitler zijn bewondering voor Breker niet weg. Brekers carrière was gelanceerd.

Nog datzelfde jaar, 1936, ontmoette Breker Albert Speer voor het eerst – waarvoor hij beelden maakt voor op de Wereldtentoonstelling in Parijs – en een jaar later, in 1937 werd Breker tot Professor benoemd. Maar met de nederlaag van Duitsland in 1945, leek er een abrupt einde te komen aan Brekers carrière.

Na de oorlog…

De eerste jaren na het einde van Wereldoorlog II leefde Breker nogal teruggetrokken. Hij maakte van de tijd, die hij afgezonderd was, wel gebruik om na te denken over zijn leven, de keuzes die hij gemaakt had enz. en om opnieuw contact te zoeken met zijn oude (Franse) vrienden, collega’s. Pas sinds de jaren 1950 liepen de opdrachten terug binnen. Deze opdrachten waren vooral inzake schilderijen, bustes (bijvoorbeeld van de Italiaanse dichter Ezra Pound en de Spaanse kunstenaar Salvador Dali) en zelfs enkele architecturale opdrachten (bijvoorbeeld het Gerling-gebouw in Keulen).

De eerste jaren na het einde van Wereldoorlog II leefde Breker nogal teruggetrokken. Hij maakte van de tijd, die hij afgezonderd was, wel gebruik om na te denken over zijn leven, de keuzes die hij gemaakt had enz. en om opnieuw contact te zoeken met zijn oude (Franse) vrienden, collega’s. Pas sinds de jaren 1950 liepen de opdrachten terug binnen. Deze opdrachten waren vooral inzake schilderijen, bustes (bijvoorbeeld van de Italiaanse dichter Ezra Pound en de Spaanse kunstenaar Salvador Dali) en zelfs enkele architecturale opdrachten (bijvoorbeeld het Gerling-gebouw in Keulen).

Pas begin de jaren 1980 werden de eerste tentoonstellingen met werken van Breker georganiseerd, al stootten deze op flinke weerstand. Zo moest een expositie in Zürich de deuren sluiten; nog een andere in Berlijn werd verstoord door zo’n 400 antifascistische demonstranten. Pas in 2006, 15 jaar na Brekers dood in 1991, organiseerde de overheid zelf een tentoonstelling met Brekers werken – hierbij refereer ik terug naar het begin van dit artikel – en, zoals ik reeds zei, lokte deze heel wat controverse uit. Doch: meer dan 35 000 mensen kwamen deze tentoonstellingen bezichtigen en de commentaren waren, over het algemeen, lovend. Dit getuigt dat sommige mensen politiek en kunst van elkaar gescheiden weten te houden; en maar goed ook: het zou immers zonde zijn indien dergelijke magnifieke werken, zoals Der Sieger, Eos of nog andere, verloren zouden gaan vanwege het verleden van haar maker.

Geschreven door Gauthier Bourgeois

Bronnen

- “Arno Breker: ein Leben für das Schöne”, Dominique Egret

- “Beelden voor de massa: kunst als wapen in het Derde Rijk”, Michel Peeters

- “Das Bildnis des Menschen im Werk von Arno Breker”, Volker Probst

- “De echo van Arno Breker: kunstenaar, nazi en/of visionair?”

- “Het Arno Breker-taboe”, Mark Schenkel

00:05 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : art, sculpture, arno breker, années 20, années 30, années 40, arts plastiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 01 mai 2011

A Arte de Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema

00:05 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : art, peinture, arts plastiques, angleterre, 19ème siècle |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 28 avril 2011

A Arte de William Bouguereau

00:05 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (2) | Tags : art, arts plastiques, peinture, 19ème siècle |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 17 avril 2011

A Arte de Lord Frederick Leighton

00:06 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : art, arts plastiques, peinture, angleterre, 19ème siècle |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 24 février 2011

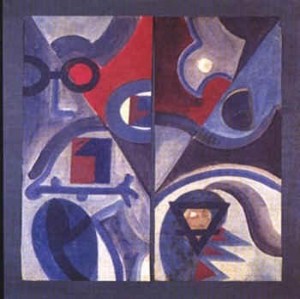

Futurisme et dadaisme chez Evola

Futurisme et dadaïsme chez Evola

Salvatore FRANCIA

Nous devons également mentionner l'influence qu'exerça sur Evola adolescent le groupe qui s'était constitué autour des revues de Giovanni Papini et du mouvement futuriste. Le jeune Evola ne tarda pas à reconnaître toutefois que l'orientation générale du futurisme ne s'accordait que fort peu avec ses propres inclinaisons. Dans le futurisme, beaucoup de choses lui déplaisaient : le sensualisme, l'absence d'intériorité, les aspects tapageurs et exhibitionnistes, l'exaltation grossière de la vie et de l'instinct, curieusement mêlée avec celle du machinisme et d'une espèce d'américanisme, même si, par ailleurs, le futurisme se référait à des formes chauvines de nationalisme.

Nous devons également mentionner l'influence qu'exerça sur Evola adolescent le groupe qui s'était constitué autour des revues de Giovanni Papini et du mouvement futuriste. Le jeune Evola ne tarda pas à reconnaître toutefois que l'orientation générale du futurisme ne s'accordait que fort peu avec ses propres inclinaisons. Dans le futurisme, beaucoup de choses lui déplaisaient : le sensualisme, l'absence d'intériorité, les aspects tapageurs et exhibitionnistes, l'exaltation grossière de la vie et de l'instinct, curieusement mêlée avec celle du machinisme et d'une espèce d'américanisme, même si, par ailleurs, le futurisme se référait à des formes chauvines de nationalisme.

Justement, à propos du nationalisme, ses divergences de vue avec les futuristes apparaissent dès le déclenchement de la première guerre mondiale, à cause de la violente campagne interventionniste déclenchée par le groupe de Papini et le mouvement futuriste. Pour Evola, il était inconcevable que tous ces gens, avec à leur tête Papini, épousassent les lieux communs patriotards les plus éculés de la propagande anti-germanique, croyant ainsi sérieusement appuyer une guerre pour la défense de la civilisation et de la liberté contre la barbarie et l'agression.

Evola, à l'époque, n'avait encore jamais quitté l'Italie et n'avait qu'un sentiment confus des structures hiérarchiques, féodales et traditionnelles présentes en Europe centrale, alors qu'elles avaient quasiment disparu du reste de l'Europe à la suite de la révolution française. Malgré l'imprécision de ses vues, ses sympathies allaient vers l'Autriche et l'Allemagne et il ne souhaitait pas l'abstention et la neutralité italiennes, mais une intervention aux côtés des puissances impériales d'Europe centrale. Après avoir lu un article d'Evola dans ce sens, Marinetti lui aurait dit textuellement : « Tes idées sont aussi éloignées des miennes que celles d'un Esquimau ».

Après 1918, Evola est attiré par le mouvement dadaïste, surtout à cause de son radicalisme. Le dadaïsme défendait une vision générale de la vie sous-tendue par une impulsion vers une libération absolue se manifestant sous des formes paradoxales et déconcertantes, accompagnées d'un bouleversement de toutes les catégories logiques, éthiques et esthétiques. « Ce qui vit en nous est de l'ordre du divin, affirmait Tristan Tzara, c'est le réveil de l'action anti-humaine ». Ou encore : « Nous cherchons la force directe, pure, sobre, unique, nous ne cherchons rien d'autre ». Le dadaïsme ne pouvait conduire nulle part : il signalait bien plutôt l'auto-dissolution de l'art dans un état supérieur de liberté. Pour Evola, c'est en cela que résidait la signification essentielle du dadaïsme. C'est ce que nous constatons en effet à la lecture de son article « Sul significato dell'arte modernissima », reproduit en appendice de ses Saggi sull'idealismo magico, publiés en 1925. En réalité, le mouvement auquel Evola avait été associé n'a réalisé que bien peu de choses. Evola en avait espéré davantage. Si le dadaïsme représentait la limite extrême et indépassable de tous les courants d'avant-garde, tout ne s'auto-consommait pas dans l'expérience d'une rupture effective avec toutes les formes d'art.

Au dadaïsme succéda le surréalisme, dont le caractère, du point de vue d'Evola, était régressif, parce que, d'une part, il cultivait une espèce d'automatisme psychique se tournant vers les strates subconscientes et inconscientes de l'être (au point de se solidariser avec le psychanalyse elle-même) et, d'autre part, se bornait à transmettre des sensations confuses venues d'un « au-delà » inquiétant et insaisissable de la réalité, sans aucune ouverture véritable vers le haut.

Il est difficile de parler de la peinture d'Evola, vu l'abstraction des sujets. En contemplant les tableaux d'Evola et en lisant ses poèmes dadaïstes, on comprend que le monde moderne, tel que le percevaient les élites des premières années de notre siècle, apparaissait comme le symbole du dénuement et de la purification. Ces élites rejetaient les oripeaux de la culture bourgeoise du XIXème et voulaient créer rapidement une « nouvelle objectivité » que certains ont cru découvrir dans le bolchevisme et d'autres dans le nazisme.

À 23 ans, Evola cesse définitivement de peindre et d'écrire des poésies. Ses intérêts le portent vers une autre sphère.

(Extrait de Il pensiero tradizionale di Julius Evola, Società Editrice Barbarossa, Milano, 1994 ; ouvrage disponible auprès de notre service librairie. Prix: 240 FB ou 45 FF, port compris).

00:05 Publié dans art, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : art, dadaïsme, futurisme, italie, julius evola, avant-gardes, tradition, traditionalisme, art, arts plastiques, peinture |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 30 décembre 2010

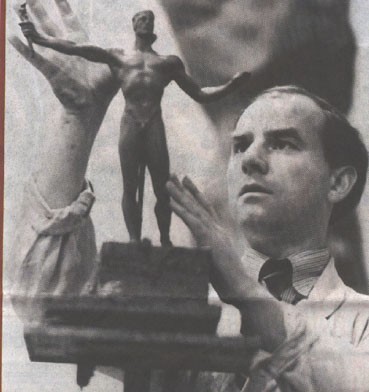

Arno Breker & the Pursuit of Perfection

Arno Breker & the Pursuit of Perfection

Jonathan BOWDEN

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Arno Breker (1900–1991) was the leading proponent of the neo-classical school in the twentieth century, but he was not alone by any stretch of the imagination. If we gaze upon a great retinue of his figurines, which can be seen assembled in the Studio at Jackesbruch (1941), then we can observe images such as Torso with Raised Arms (1929), the Judgment of Paris, St. Mathew (1927), and La Force (1939). All of these are taken from the on-line museum and linkage which is available at:

http://ilovefiguresculpture.com/masters/german/breker/bre...

The real point to make is that these are dynamic pieces which accord with over three thousand years of Western effort. They are not old-fashioned, Reactionary, bombastic, “facsimiles of previous glories,” mere copies or the pseudo-classicism of authoritarian governments in the twentieth century (as is usually declared to be the case). Joseph Stalin approached Breker after the Second European Civil War (1939–1945) in order to explore the possibility for commissions, but insisted that they involved castings which were fully clothed. At first sight, this was an odd piece of Soviet prudery — but, in fact, politicians as diverse as John Ashcroft (Bush’s top legal officer) and Tony Blair refused to be photographed anywhere near classical statuary for fear that any proximity to nudity (without Naturism) might lead to their tabloid down-fall.

All of Breker’s pieces have precedents in the ancient world, but this has to be understood in an active rather than a passive or re-directed way. If we think of the Hellenism which Alexander’s all-conquering armies inspired deep into Asia Minor (and beyond), then pieces like the Laocoön at the Vatican or the full-nude portrait of Demetrius the First of Syria, whose modelling recalls Lysippus’ handling, are definite precursors. (This latter piece is in the National Museum in Rome.) Yet Breker’s work is quite varied, in that it contains archaic, semi-brutalist, unshorn, martial relief and post-Cycladic material. There is also the resolution of an inner tension leading to a Stoic calm, or a heroic and semi-religious rest, that recalls the Mannerist art of the sixteenth century. Certain commentators, desperate for some sort of affiliation to modernism in order to “save” Breker, speak loosely of Expressionist sub-plots. This is quite clearly going too far — but it does draw attention to one thing . . . namely, that many of these sculptures indicate an achievement of power, a rest or beatitude after turmoil. They are indicative of Hemingway’s definition of athletic beauty — that is to say, grace under pressure or a form of same.

All of Breker’s pieces have precedents in the ancient world, but this has to be understood in an active rather than a passive or re-directed way. If we think of the Hellenism which Alexander’s all-conquering armies inspired deep into Asia Minor (and beyond), then pieces like the Laocoön at the Vatican or the full-nude portrait of Demetrius the First of Syria, whose modelling recalls Lysippus’ handling, are definite precursors. (This latter piece is in the National Museum in Rome.) Yet Breker’s work is quite varied, in that it contains archaic, semi-brutalist, unshorn, martial relief and post-Cycladic material. There is also the resolution of an inner tension leading to a Stoic calm, or a heroic and semi-religious rest, that recalls the Mannerist art of the sixteenth century. Certain commentators, desperate for some sort of affiliation to modernism in order to “save” Breker, speak loosely of Expressionist sub-plots. This is quite clearly going too far — but it does draw attention to one thing . . . namely, that many of these sculptures indicate an achievement of power, a rest or beatitude after turmoil. They are indicative of Hemingway’s definition of athletic beauty — that is to say, grace under pressure or a form of same.

This is quite clearly missed by the well-known interview between Breker and Andre Muller in 1979 in which a Rottweiler of the German press (of his era) attempts to spear Breker with post-war guilt. Indeed, at one dramatic moment in the dialogue between them, Muller almost breaks down and accuses Breker of producing necrophile masterpieces or anti-art (sic). What he means by this is that Breker is artistically glorifying in war, slaughter, and death. As a Roman Catholic teacher of acting once remarked to me, concerning the poetry of Gottfried Benn, it begins with poetry and ends in slaughter. Yet the answer to this ethical ‘plaint is that it was ever so. Artistic works have always celebrated the soldierly virtues, the martial side of the state and its prowess, and all of the triumphalist sculpture on the Allied side (American, Soviet, Resistance-oriented in France, etc. . . .) does just that. As Wyndham Lewis once remarked in The Art of Being Ruled, the price of civility in a cultivated dictatorship (he was thinking of Mussolini’s Italy) might well be the provision of an occasional Gladiator in pastel . . . so that one could be free from communist turmoil, on the one hand, and able to continue one’s work in serenity, on the other. Doesn’t Hermann Broch’s great post-modern work, The Death of Virgil, which dips in and out of Virgil’s consciousness as he dies, rather like music, not speculate on his subservience to the Caesars and his pained confusion about whether the Aeneid should be destroyed? It survived intact.

Nonetheless, the interview provides a fascinating crucible for the clash of twentieth century ideas in more ways than one. At one point Muller’s diction resembles a piece of dialogue from a play by Samuel Beckett (say End-Game or Fin de Partie); maybe the stream-of-consciousness of the two tramps in Waiting for Godot. For, whether it’s Vladimir or Estragon, they might well sound like Muller in this following exchange. Muller indicates that his view of Man is broken, crepuscular, defeated, incomplete and misapplied — he congenitally distrusts all idealism, in other words. Mankind is dung — according to Muller — and coprophagy the only viable option. Breker, however, is of a fundamentally optimistic bent. He avers that the future is still before us, his Idealism in relation to Man remains unbroken and that a stratospheric take-off into the future remains a possibility (albeit a distant one at the present juncture).

Another interesting exchange between Muller and Breker in this interview concerns the Shoah. (It is important to realise that this highly-charged chat is not an exercise in reminiscence. It concerns the morality of revolutionary events in Europe and their aftermath.) By any stretch, Breker declares himself to be a believer and that the criminal death through a priori malice of anyone, particularly due to their ethnicity, is wrong. At first sight this appears to be an unremarkable statement. A bland summation would infer that the neo-classicist was a believer in Christian ethics, et cetera. . . . Yet, viewed again through a different premise, something much more revolutionary emerges. Breker declares himself to be a “believer” (that is to say, an “exterminationist” to use the vocabulary of Alexander Baron); yet even to affirm this is to admit the possibility of negation or revision (itself a criminal offense in the new Germany). For the most part contemporary opinion mongers don’t declare that they believe in Global warming, the moon shot, or the link between HIV and AIDS — they merely affirm that no “sane” person doubts it.

Another interesting exchange between Muller and Breker in this interview concerns the Shoah. (It is important to realise that this highly-charged chat is not an exercise in reminiscence. It concerns the morality of revolutionary events in Europe and their aftermath.) By any stretch, Breker declares himself to be a believer and that the criminal death through a priori malice of anyone, particularly due to their ethnicity, is wrong. At first sight this appears to be an unremarkable statement. A bland summation would infer that the neo-classicist was a believer in Christian ethics, et cetera. . . . Yet, viewed again through a different premise, something much more revolutionary emerges. Breker declares himself to be a “believer” (that is to say, an “exterminationist” to use the vocabulary of Alexander Baron); yet even to affirm this is to admit the possibility of negation or revision (itself a criminal offense in the new Germany). For the most part contemporary opinion mongers don’t declare that they believe in Global warming, the moon shot, or the link between HIV and AIDS — they merely affirm that no “sane” person doubts it.

Similarly, even Muller raises the differentiation in Breker’s work over time. This is particularly so after the twin crises of 1945 and 1918 and the fact that these were the twin Golgothas in the European sensibility — both of them taking place, almost as threnodies, after the end of European Civil Wars. Germany and its allies taking the role of the Confederacy on both occasions, as it were. Immediately after the War — and amid the kaos of defeat and “Peace” — Breker produced St. Sebastien in 1948, St. George (as a partial relief) in 1952, and the more reconstituted St. Christopher in 1957. (One takes on board — for all sculptors — the fact that the Church is a valuable source of commissions in stone during troubled times.) All of this led to a celebration of re-birth and the German economic miracle of recovery in his unrealized Resurrection (1969) which was a sketch or maquette to the post-war Chancellor Adenauer. Saint Sebastien is interesting in its semi-relief quality which is the nearest that Breker ever comes to a defeated hero or — quite possibly — the mortality which lurks in victory’s strife. Interestingly enough, a large number of aesthetic crucifixions were produced around the middle of the twentieth century. One thinks (in particular) of Buffet’s post-Christian and existential Pieta, Minton’s painting in the ‘fifties about the Roman soldiery, post-Golgotha, playing dice for Christ’s robes, or Bacon’s screaming triptych in 1947; never mind Graham Sutherland’s reconstitution of Coventry Cathedral (completely gutted by German bombing); and an interesting example of an East German crucifixion.

This is a fascinating addendum to Breker’s career — the continuation of neo-classicism, albeit filtered through socialist realism, in East Germany from 1946–1987. An interesting range of statuary was produced in a lower key — a significant amount of it not just keyed to Party or bureaucratic purposes. In the main, it strikes one as a slightly crabbed, cramped, more restricted, mildly cruder and more “proletarianized” version of Breker and Kolbe. But some decisive and significant work (completely devalued by contemporary critics) was done by Gustav Seitz, Walter Arnold, Heinrich Apel, Bernd Gobel, Werner Stotzer, Siegfried Schreiber, and Fritz Cremer. His crucifixion in the late ‘forties has a kinship (to my mind) with some of Elisabeth Frink’s pieces — it remains a neo-classic form whilst edging close to elements of modernist sculpture in its chthonian power and deliberate primitivism. A part of the post-maquette or stages of building up the Form remains in the final physiology, just like Frink’s Christian Martyrs for public display. Perhaps this was the nearest a three-dimensional artist could get to the realization of religious sacrifice (tragedy) in a communist state.

Anyway, and to bring this essay to a close, one of the greatest mistakes made today is the belief that the Modern and the Classic are counterposed, alienated from one another, counter-propositional and antagonistic. The Art of the last century and a half is an enormous subject (it’s true) yet Arno Breker is one of the great Modern artists. One can — as the anti-humanist art collector Bill Hopkins once remarked — be steeped both in the Classic and the Modern. Living neo-classicism is a genuine contemporary tradition (post Malliol and Rodin) because photography can never replace three-dimensionality in form or focus. Above all, perhaps it’s important to make clear that Breker’s work represents extreme heroic Idealism . . . it is the fantastication of Man as he begins to transcend the Human state. In some respects, his work is a way-station towards the Superman or Ultra-humanite. This remains one of the many reasons why it sticks in the gullet of so many liberal critics!

One will not necessarily reassure them by stating that Breker’s monumental sculptures during his phase of Nazi Art were modeled (amongst other things) on the Athena Parthenos. The original was over forty feet high, came constructed in ivory and gold, and was made during the years 447–439 approximately. (The years relate to Before the Common Era, of course.) The Goddess is fully armoured — having been born whole as a warrior-woman from Zeus’ head. There may be Justice but no pity. A winged figure of Victory alights on her right-hand; while the left grasps a shield around which a serpent (knowledge) writhes aplenty. A re-working can be seen in John Barron’s Greek Sculpture (1965), but perhaps the best thing to say is that the heroic sculptor of Man’s form, Steven Mallory, in Ayn Rand’s Romance The Fountainhead is clearly based on Thorak: Breker’s great rival. Yet the “gold in the furnace” producer of a Young Woman with Cloth (1977) remains to be discovered by those tens of thousands of Western art students who have never heard of him . . . or are discouraged from finding out.

00:05 Publié dans art, Histoire, Hommages | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : arno breker, hommages, art, sculpture, arts plastiques, allemagne, art monumental, sculpture classique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 02 décembre 2010

La CIA, mécène de l'expressionnisme abstrait

|

La CIA, mécéne de l’expressionnisme abstrait Ex: http://www.voltairenet.org/ L’historienne Frances Stonor Saunders, auteure de l’étude magistrale sur la CIA et la guerre froide culturelle, vient de publier dans la presse britannique de nouveaux détails sur le mécénat secret de la CIA en faveur de l’expressionnisme abstrait. La Repubblica s’interroge sur l’usage idéologique de ce courant artistique. |

|

|

Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko. Rien moins que faciles et même scandaleux, les maîtres de l’expressionnisme abstrait. Un courant vraiment à contre-courant, une claque aux certitudes de la société bourgeoise, qui pourtant avait derrière elle le système lui-même. Car, pour la première fois, se confirme une rumeur qui circule depuis des années : la CIA finança abondamment l’expressionnisme abstrait. Objectif des services secrets états-uniens : séduire les esprits des classes qui étaient loin de la bourgeoisie dans les années de la Guerre froide. Ce fut justement la CIA qui organisa les premières grandes expositions du New American Painting, qui révéla les œuvres de l’expressionnisme abstrait dans toutes les principales villes européennes : Modern Art in the United States (1955) et Masterpieces of the Twentieth Century (1952). Donald Jameson, ex fonctionnaire de l’agence, est le premier à admette que le soutien aux artistes expressionnistes entrait dans la politique de la « laisse longue » (long leash) en faveur des intellectuels. Stratégie raffinée : montrer la créativité et la vitalité spirituelle, artistique et culturelle de la société capitaliste contre la grisaille de l’Union soviétique et de ses satellites. Stratégie adoptée tous azimuts. Le soutien de la CIA privilégiait des revues culturelles comme Encounter, Preuves et, en Italie, Tempo presente de Silone et Chiaramonte. Et des formes d’art moins bourgeoises comme le jazz, parfois, et, justement, l’expressionnisme abstrait. Les faits remontent aux années 50 et 60, quand Pollock et les autres représentants du courant n’avaient pas bonne presse aux USA. Pour donner une idée du climat à leur égard, rappelons la boutade du président Truman : « Si ça c’est de l’art, moi je suis un hottentot ». Mais le gouvernement US, rappelle Jameson, se trouvait justement pendant ces années-là dans la position difficile de devoir promouvoir l’image du système états-unien et en particulier d’un de ses fondements, le cinquième amendement, la liberté d’expression, gravement terni après la chasse aux sorcières menée par le sénateur Joseph McCarthy, au nom de la lutte contre le communisme.

Pour ce faire, il était nécessaire de lancer au monde un signal fort et clair de sens opposé au maccarthysme. Et on en chargea la CIA, qui, dans le fond, allait opérer en toute cohérence. Paradoxalement en effet, à cette époque l’agence représentait une enclave « libérale » dans un monde qui virait décisivement à droite. Dirigée par des agents et salariés le plus souvent issus des meilleures universités, souvent eux-mêmes collectionneurs d’art, artistes figuratifs ou écrivains, les fonctionnaires de la CIA représentaient le contrepoids des méthodes, des conventions bigotes et de la fureur anti-communiste du FBI et des collaborateurs du sénateur McCarthy. « L’expressionnisme abstrait, je pourrais dire que c’est justement nous à la CIA qui l’avons inventé —déclare aujourd’hui Donald Jameson, cité par le quotidien britannique The Independent [1]— après avoir jeté un œil et saisi au vol les nouveautés de New York, à Soho. Plaisanteries à part, nous avions immédiatement vu très clairement la différence. L’expressionnisme abstrait était le genre d’art idéal pour montrer combien était rigide, stylisé, stéréotypé le réalisme socialiste de rigueur en Russie. C’est ainsi que nous décidâmes d’agir dans ce sens ». Mais Pollock, Motherwell, de Kooning et Rothko étaient-ils au courant ? « Bien sûr que non —déclare immédiatement Jameson— les artistes n’étaient pas au courant de notre jeu. On doit exclure que des gens comme Rothko ou Pollock aient jamais su qu’ils étaient aidés dans l’ombre par la CIA, qui cependant eut un rôle essentiel dans leur lancement et dans la promotion de leurs œuvres. Et dans l’augmentation vertigineuse de leurs gains ».

[1] « Modern art was CIA ’weapon’ », par Frances Stonor Saunders, The Independent, 22 octobre 2010.

|

00:20 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | Tags : art, peinture, arts plastiques, expressionnisme, cia, manipulation médiatiques, art moderne, art abstrait, impérialisme, etats-unis |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

L'ombra progressista della CIA

|

L'ombra progressista della CIA |

|

L'Agenzia sostenne l'espressionismo astratto di Pollock & co Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko. Per niente facili e anche scandalosi, i maestri dell'Espressionismo astratto. Corrente davvero controcorrente, una spallata alle certezze estetiche della società borghese, che però aveva dietro il sistema stesso. Perché, per la prima volta, trova conferma una voce circolata per anni: la Cia finanziò abbondantemente l'Espressionismo astratto. Obiettivo dell'intelligence Usa, sedurre le menti delle classi lontane dalla borghesia negli anni della Guerra Fredda. Fu proprio la Cia a organizzare le prime grandi mostre del "new american painting", che rivelò le opere dell'Espressionismo astratto in tutte le principali città europee: "Modern art in the United States" (1955) e "Masterpieces of the Twentieth Century" (1952). Donald Jameson, ex funzionario dell'agenzia, è il primo ad ammettere che il sostegno agli artisti espressionisti rientrava nella politica del "guinzaglio lungo" (long leash) in favore degli intellettuali. Strategia raffinata: mostrare la creatività e la vitalità spirituale, artistica e culturale della società capitalistica contro il grigiore dell'Uonione sovietica e dei suoi satelliti. Strategia adottata a tutto campo. Il sostegno della Cia privilegiava riviste culturali come "Encounter", "Preuves" e, in Italia, "Tempo presente" di Silone e Chiaromonte. E forme d'arte meno borghesi come il jazz, talvolta, e appunto, l'espressionismo astratto.

|

Noreporter - Tutti i nomi, i loghi e i marchi registrati citati o riportati appartengono ai rispettivi proprietari. È possibile diffondere liberamente i contenuti di questo sito .Tutti i contenuti originali prodotti per questo sito sono da intendersi pubblicati sotto la licenza Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs-NonCommercial 1.0 che ne esclude l'utilizzo per fini commerciali.I testi dei vari autori citati sono riconducibili alla loro proprietà secondo la legacy vigente a livello nazionale sui diritti d'autore.

00:20 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : art, arts plastiques, peinture, expressionnisme, expressionnisme abstrait, art moderne, art abstrait, cia, manipulation médiatique, etats-unis, services secrets |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 31 octobre 2010

Archère par Dragos Kalajic

En souvenir de nos universités d'été communes, cher Dragos, et de notre intervention à Milan en 1999 contre l'intervention de l'OTAN en Serbie!

Que vive notre amitié au-delà de la mort !

00:10 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : serbie, art, arts plastiques, peinture |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 30 octobre 2010

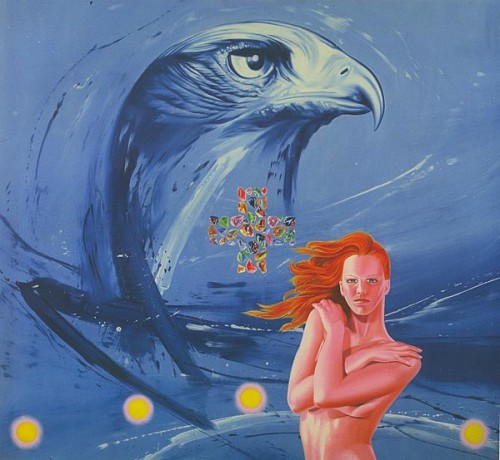

Aigle impérial par Dragos Kalajic

En souvenir de notre camarade serbe Dragos Kalajic, qui a quitté nos rangs trop tôt!

Notre souvenir ému !

00:10 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | Tags : serbie, tradition, art, peinture, arts plastiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 11 septembre 2010

Konstantin Vasiliev: Aigle

00:10 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : russie, peinture, art, arts plastiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 01 septembre 2010

Kunstexpositie: Magievan de Herinnering

| Kunstexpositie: Magie van de Herinnering |

Op zondag 5 september 2010 zal Dr. Pavel Tulaev, directeur van het Russisch tijdschrift "Atheneum", in Vlaanderen te gast zijn om enkele hedendaagse Russische schilderijen voor te stellen. Op zondag 5 september 2010 zal Dr. Pavel Tulaev, directeur van het Russisch tijdschrift "Atheneum", in Vlaanderen te gast zijn om enkele hedendaagse Russische schilderijen voor te stellen.De echte werken naar hier halen is op zo'n korte tijd onbegonnen werk. Daarom zullen de bezoekers kennis kunnen maken met prachtige reproducties. Deze reproducties zullen ter plaatse aan een prijsje aangekocht kunnen worden. Dr. Pavel Tulaev bezoekt Vlaanderen nadat hij in Italië deelneemt aan het World Congress for Ethnic Religions. U krijgt, met de medewerking van Euro-Rus, een unieke gelegenheid om met Dr. Pavel Tulaev en de werken van Russsische kunstenaars kennis te maken. De gallerijtentoonstelling vindt plaats te Dendermonde, zaal-taverne 't Peird, Kasteelstraat 1, vlakbij de Grote markt en op korte wandelafstand van het station. De deuren gaan open om 11u00. Dr.Pavel Tulaev zal het woord nemen om 11u30. De gallerijtentoonstelling eindigt om 16u00. Het wordt voor u zeker en vast een interessante en leuke zondagmiddag. Wij hopen u dan in Dendermonde te mogen begroeten, Euro-Rus ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Dr. Pavel Tulaev is de drijvende kracht achter het Russischtalige tijdschrift "Atheneum", reeds in 20 verschillende landen verkrijgbaar en verkocht. Hij zag het levenslicht op 20 februari 1959 te Krasnodar, Zuid-Rusland. In Moskou studeerde hij in 1982 af aan aan de Moskouse linguistische staatsuniversiteit met specialisaties voor Spaans, Engels en Frans. Hij is de drijvende kracht achter deze nieuw rechtse Russische denktank, die zich buigt over vraagstukken die de Russische, Slavische en Indo-Europese volkeren aangaan. Hij schreef zeer interessante en aan te raden stukken over Rusland, de Slaven, de Vierde Wereldoorlog, e.a. Verschillende werden reeds op de pagina's van Euro-Rus gepubliceerde. Hij publiceerde reeds meer dan 100 stukken over Rusland, Europa, Latijns-Amerika en de Verenigde Staten. Hij gaf reeds verschillende boeken uit : «Крест над Крымом» (1992), «Семь лучей» (1993), «К пониманию Русского» (1994), «Консервативная Революция в Испании» (1994), «Франко: вождь Испании» (1998), «Венеты: предки славян» (2000), «Афина и Атенеи» (2006), «Русский концерт Анатолия Полетаева» (2007), «Родные Боги в творчестве славянских художников» (2008). In niet-Russische talen publiceerde hij volgende teksten : Rusia y España se descubren una a otra. Sevilla, 1992; Sobor and Sobornost, – "Russian Studies in Filosophy", N.Y., 1993, vol. 31, № 4; Deutschen und Russen – Partneur mit Zukunft? – "Nation & Europa", 1998, № 11/12; Les guerres de nouvelles génération, – "Nouvelles de Synergies Européennes", Brussel, 1999, № 39; Intretien avec Pavel Toulaev, – Ibidem, № 40; Atak I zwyciestwo kazdego dnia.– "ODALA", SZCZECIN, 1999, numer V; Veneti: predniki slovanov.– Tretji venetski zbornik – Editiones Veneti, Ljubljana 2000; Сiм променiв – «Сварог», Киiв, 2003; Венети (превео са руског Владимир Карич), Београд, 2004; Pavel Tulaev: «Deutschland und Russland», "Der Vierte Weltkrieg" – DEUTSCHLAND UND RUSSLAND. Deutsche Sonderausgabe der Zeitschrift ATHENAEUM, Moskau, 2005; BUYAN SPEAKS. An interview with Pavel Tulaev conducted by Constantin von Hoffmeister for National Vanguard (USA), 2005; Рiдним богиням i берегиням – «Сварог», Киiв, 2006; Pavel Tulaev «Euro-Russia in the context of World War IV», Moscow, 2006; Pavel Toulaev «L'Euro-Russie dans le contexte de la Quatrieme Guerre Mondiale» Moscau, 2006; «La Russie: le grand retour» – Reflechir & Agir (Toulouse) №23, 2006; Pavel Tulaev «España y Rusia: dos suertes analogas» Discurso pronunciado en Madrid 4.11.2006; Павел Тулаев «Русия и Европа в условията на Четвърта Световна Война» 2006; ИнтервЉу са Павелом ТулаЉевом БУ£АН ГОВОРИ! (2007); Interview with Andrej Sletcha (Prage, 2008); etc. Ook organiseerde hij verschillende congressen, waaronder het succesvolle congres van 2007 te Moskou "Europa en Rusland, verschillende perspectieven" waar Kris Roman Euro-Rus vertegenwoordigde. Van 17 tot en met 25 juni 2010 organiseerde Dr. Pavel Tulaev een tentoonstelling van Russisch-Slavische meesterwerken. Met hetzelfde doel bevond hij zich reeds in West-Europese steden zoals Parijs. http://www.ateney.ru/art/index.htm |

18:23 Publié dans art, Evénement | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : rusie, art, peinture, arts plastiques, tradition, traditions, traditionalisme, paganisme, ethnologie, anthropologie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook